Travel through time...

INTRODUCTION

Both Sevilla and Warmhoek form part of the Cradle of Human Culture route “The Artists Journey”. Both trails include numerous individual rock art sites left behind by past inhabitants of the landscape and are well known for the high quality and fascinating images that are depicted here. The rock art found here is intimately associated with the area in which they are located and the virtual tours provide a sense of this cultural landscape.

This project was conducted in conjunction with the Clanwilliam Living Landscape Project. The Living Landscape Project has successfully used the Clanwilliam landscape as a framework for teaching in local schools and developing sustainable business ideas for local people. The programme has created an archive of historical, archaeological and environmental information with links to a job creation initiative, a new schools curriculum and new heritage legislation.

The Sevilla Trail is owned and managed by the Strauss family at Travellers Rest. It has become one of South Africa’s most well-known rock art trails and is located in a mecca for bouldering and climbers.

Warmhoek

Sevilla

The 5 km trail winds along the Brandewyn River and visits 9 sites containing San rock paintings,the indigenous people who inhabited the area for thousands of years. The Sevilla Rock Art Trail offers some of the finest examples of rock art in the district and a fascinating glimpse into the world of these early inhabitants. The trail is located on a farm known as Travellers Rest which is open to the public.ROCK ART & ARCHAEOLOGY OF THE WESTERN CAPE

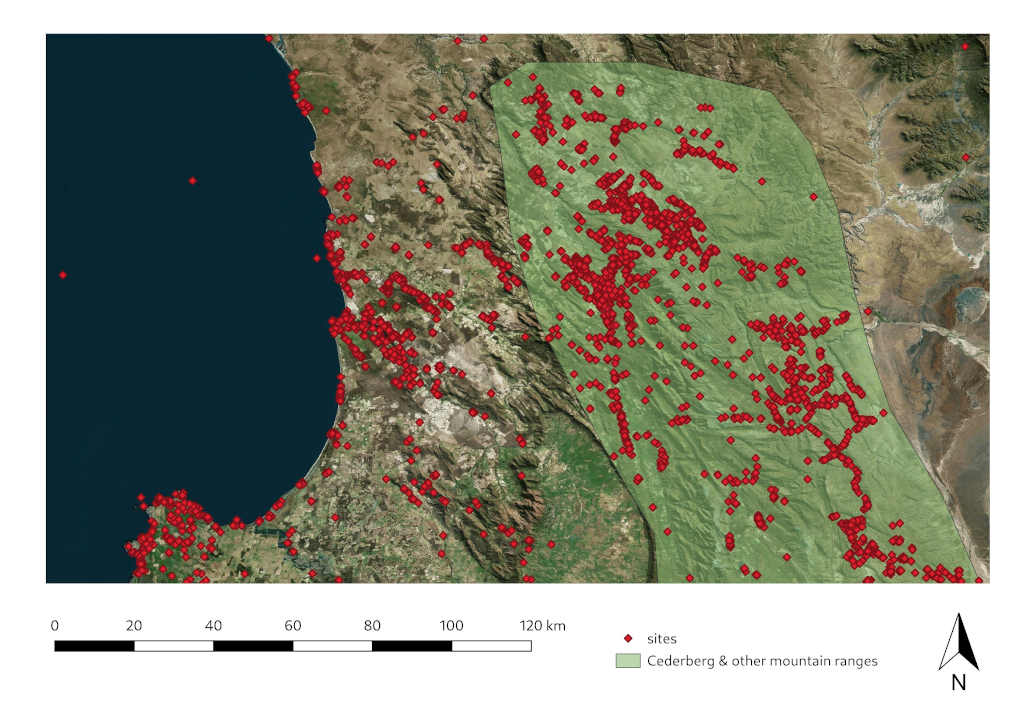

The Western Cape of South Africa has been inhabited by humans and their ancestors for at least a million years. Earlier Stone Age artefacts date to between about 2 million and 200,000 years ago. These hunter-gatherers apparently did not make rock paintings. Middle Stone Age artefacts have also been found but they are not directly linked to the artists responsible for rock paintings in the region.

From about 40,000 years ago, the Later Stone Age people living in the Western Cape were regularly making artefacts like bows and arrows, digging stick weights, ostrich eggshell beads and other items that were still being made by San hunter-gatherers at the time of European contact in the seventeenth century (1600s). It was during the Later Stone Age that most of the rock paintings were made in the Western Cape.

Rock paintings can be dated if the paint had an organic ingredient like blood or egg or plant juice, but in many cases there is not enough of these ingredients left to get a reliable age. Detailed study of the paintings over the past century has nevertheless allowed for a general sequence to be identified based on which images were painted first (the fine line humans and animals by the San) and which were painted later (the handprints and finger paintings by the Khoe), followed by colonial images of people with horses, guns and hats. Fine line paintings are generally associated with Later Stone Age San hunter-gatherers. The oldest dated fine line images in the Western Cape are at least 3500 years old and older paintings may not have survived, or have not been found in a dateable context.

For many years it was thought that the paintings were literal depictions of the landscape in which hunter-gatherers lived. It is now known that the art is more complex than this and that it was produced within a number of important ritual contexts, such as healing, rain-making and the initiation of boys and girls into adulthood. The art therefore is religious and relates to complex beliefs and practices. Rock paintings are the work of the ancestors of San hunter-gatherers, Khoe pastoralists and people of the recent colonial period. This art includes a wide range of images, types, motifs and themes. This diversity can be reduced to a few broad rock art groups or traditions. In chronological order, these are referred to as:

- Fine line images

- A range of finger-painted images including dots and lines as well as various types of handprints

- Images of colonial people, wagons and horses

- Historical graffiti

Fine-line images are the oldest images generally identified as they lie beneath later images. The remnants of images of eland are also included in this category of rock art. The eland are sometimes difficult to identify as only the red or yellow ochre remains of what was originally a multi-coloured image with white and black highlights and shading. The white and black pigments tend to wear away more quickly than the red and yellow ochre pigments which is why all that is left of the eland are blobs of colour.

The original paint was made of organic materials including red and yellow ochre.

Paintings that tend to depict more recent images such as wagons, horses and feathered hats often look very different to earlier fine-lined images. Many such images have clearly been created using the finger as a paintbrush resulting in thicker-lines and more crude-looking images.

In addition to the eland, other antelope as well as some indeterminate other animals can be found. Images of other animals are also known, such as fish, elephants and others. Images of fat-tailed sheep assist in dating rock art sites as this species is known to have arrived in this part of South Africa approximately 2000 years ago.

BASIC DO’S AND DON’TS FOR ROCK ART CONSERVATION

The following guidelines are widely accepted behaviour for visitors to rock art sites – both paintings and engravings.

• Enjoy the rock art and behave as you would in an art gallery. The longer you look at the paintings or engravings, the more you will see.

• Do not touch the paintings. Your fingers leave behind traces of oil and dirt that builds up and cannot be removed.

• Never put water or any other substance on painted surfaces to enhance the colour or detail. It causes salts to be drawn to the surface and they cannot be removed. Photos of faded paintings can be digitally enhanced and this is much better than wetting the originals.

• It is an offence in terms of the National Heritage Resources Act (No. 25 of 1999) to write on rock shelter walls, damage or “touch up” paintings or engravings. It alters the significance of the original art and spoils the experience for other visitors. If convicted of this offence, you could be liable for a fine of between R10,000 and R100,000.

• Avoid stirring up dust when you visit a painted rock shelter as the dust adheres to the rock walls and is difficult to remove. If you are going to spend some time in a rock shelter, put down a ground sheet to control dust and avoid disturbing archaeological deposits.

• Trim vegetation away from painted surfaces to stop branches brushing against paintings and to reduce the damaging effects of veld fires.

• Remove all litter after visiting a rock art site.

• Visitors to rock shelters should remove back packs to avoid their brushing against painted surfaces.

• Do not make fires in or near painted rock shelters as the smoke and cooking fumes can damage the art and discolour the rock walls.

• If you are obliged to seek shelter overnight in a rock art site, avoid leaving candle wax on rock surfaces.

The following basic guidelines are useful for the owners of properties with rock art.

• A permit must be obtained from the relevant provincial heritage resources authority for any interventions such as installation of fences, boardwalks or information boards at a rock art site.

• Seek advice from the provincial heritage resources authority or a rock art specialist if you wish to open rock art sites to the public.

• Avoid placing rubbish bins in or near to painted rock shelters as they attract animals and are often overturned, spreading the litter.

• Train a guide to take visitors to rock art sites or print a leaflet with clear instructions for all visitors.

***Summarised from the Do’s and Don’ts approved by SAHRA (the South African Heritage Resources Agency).***

tHEMES IN THE PAINTINGS

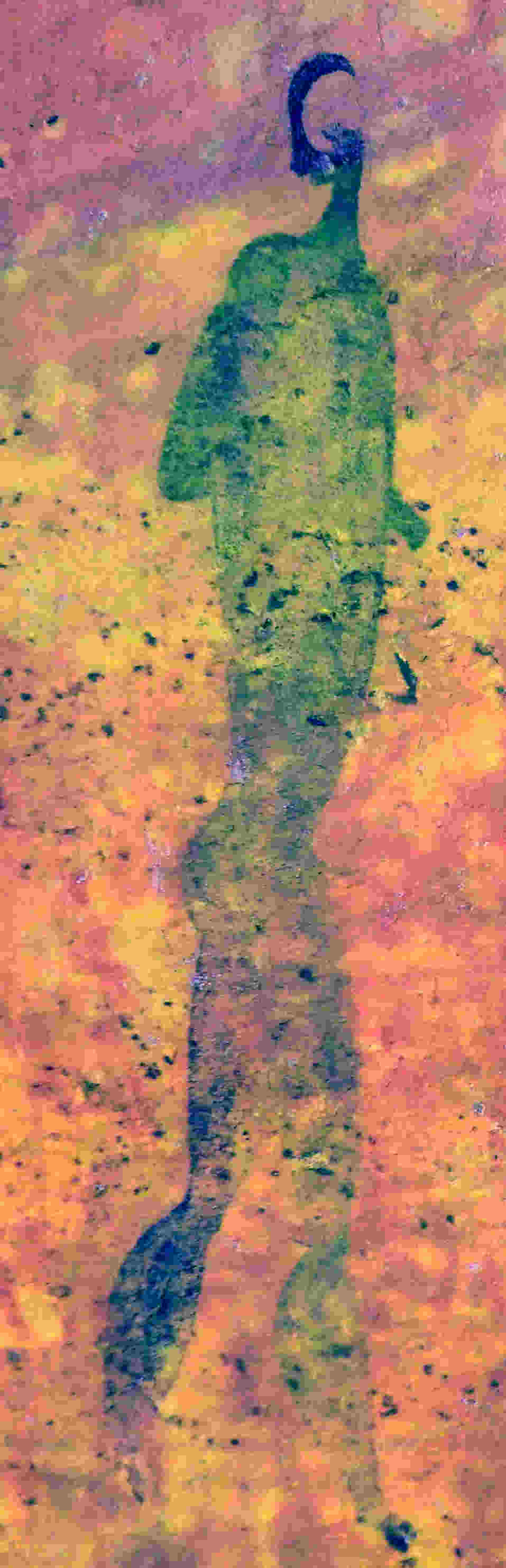

Many of the paintings of people along the trail have characteristic "hook heads". This is not fanciful art; the red ochre has lasted longer than the pale colour that once filled in their faces. This "faded" phenomenon can also be seen in animals, leaving the false impression that they were incomplete.

Therianthropes are representations of people with animal features who are experiencing trance. These features include hoofs, antelope heads, and tusks and so forth. Moreover, people are also painted combined with a range of creatures such as elephants, baboons, antelopes and birds.

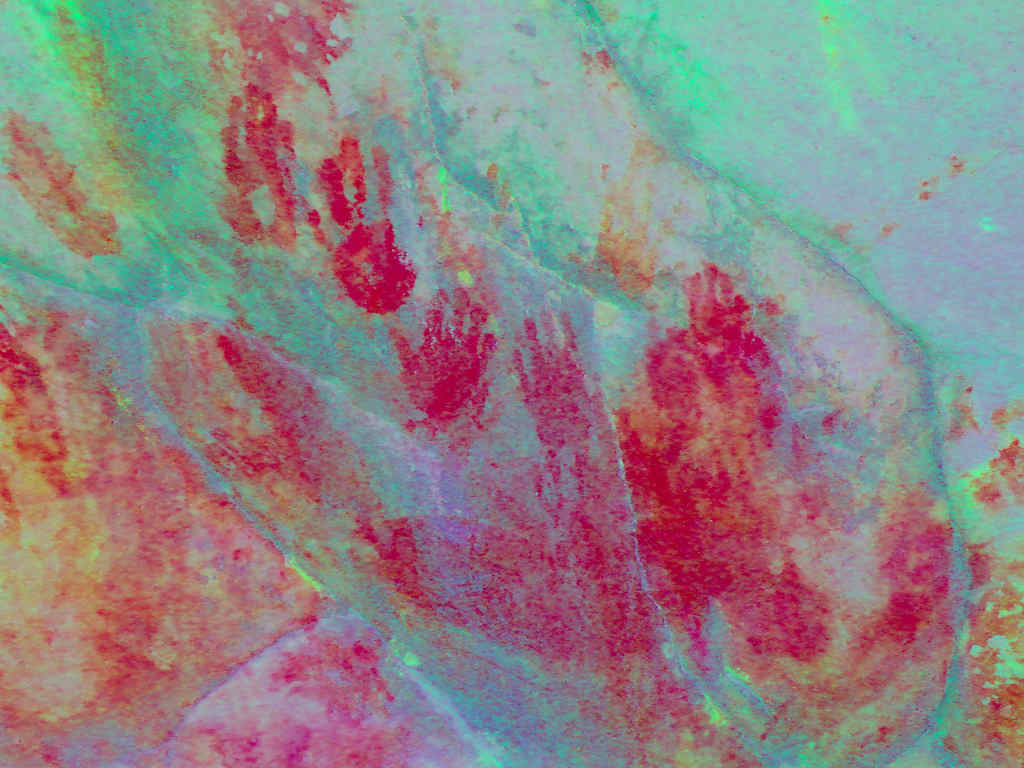

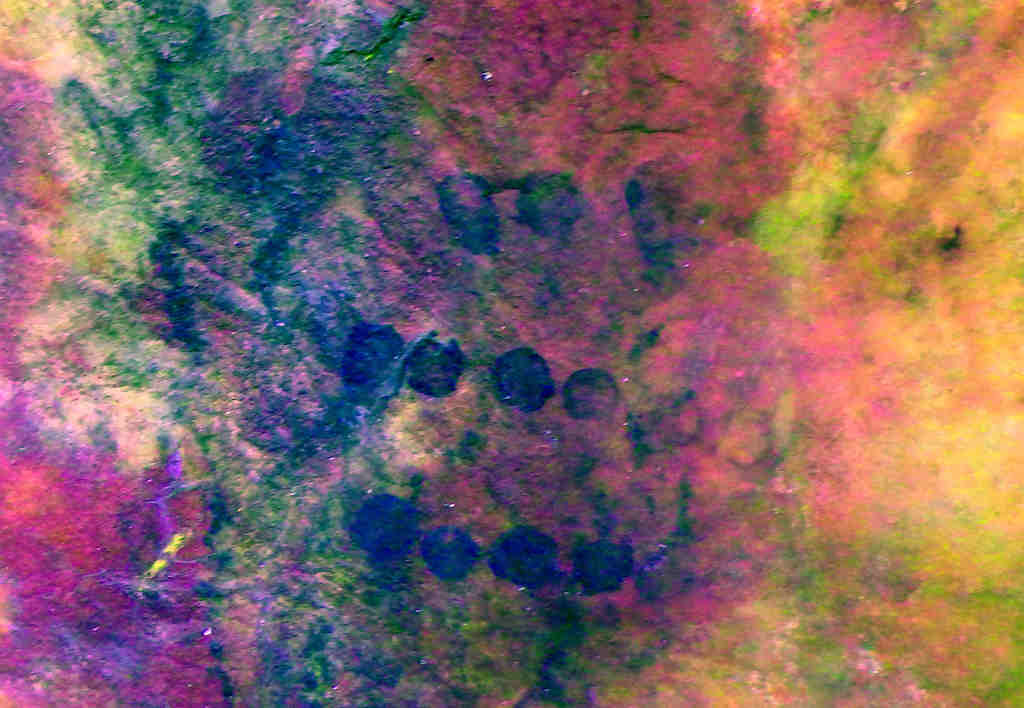

Hand prints are also often found at rock art sites in the Cederberg. These prints were made by covering the hand with ochre pigment and then using a fingernail or stick to carve patterns in the ochre before placing the hand on the surface of the cave wall to leave a print. It is hypothesised that, due to their general size, these prints belong to sub-adults, ie. young boys and girls who have left their mark as, possibly, part of a coming of age ceremony. In addition, you may also find many finger dots, indeterminate blobs of colour, wavy lines, circles and patterns of lines and dots.

The trance dance is the San's most important religious ritual, and an understanding of its various features and purposes is an essential key to appreciate the art. For the San, trance is the spirit world; it is here that they heal the sick, remonstrate with malevolent spirits, and go on out-of-body journeys. The southern San also believed that shamans could make rain and guide antelope herds into the hunters' ambush. Moreover, the San saw parallels between the behaviour of a dying antelope, especially an eland, and a shaman ‘dying' (dying is used in a metaphorical sense, meaning to enter the spirit world) in trance.

In San rock art, paintings of people carry a variety of equipment, such as arrows, bags, bows, quivers and digging sticks.

ABOUT

PROFESSOR JOHN PARKINGTON, NARRATOR

Image enhancements were carried out using DStretch which is a program designed to bring out faint pictographs that are invisible to the naked eye. DStretch was written by Jon Harman.

The images of the rock art included in both virtual tours have been processed using DStretch in order to highlight pigments that are no longer visible to the naked eye, and so enhance the experience of visiting the rock art sites.

BOOKS BY JOHN PARKINGTON

Kaggan's Grief and the Marriage of Meat. 2000. By John Parkington and Pippa Skotnes

The Mantis, the Eland and the Hunter. 2002. By John Parkington

Cederberg Rock Paintings. 2003. By John Parkington

San Rock Engravings: Marking the Karoo Landscape. 2010. By John Parkington and Neil Rusch

First People Ancestors of the San. 2015. By John Parkington and Nonhlanhla Dlamini

CONTENT DEVELOPMENT

TECHNOLOGY

Wide angle, high resolution panorama images have been captured of the rock art sites located along the Sevilla and Warmhoek trails. These individual images have been stitched together to create panoramic images for each of the captured positions. The panoramas have been integrated into a panorama tour of the rock art trails along with close up images of the rock art using 3DVista.

The panoramas are viewed on a 2D screen, and the panoramas are able to be rotated to achieve the full panoramic effect. In each panorama there are placed hotspots which show where there are other panoramas available. Clicking on the hotspot will jump the user to the chosen panorama. Additionally there are clickable icons inside the panoramas with links to information in the form of text, audio, or video. The user is able to explore and learn about the rock art sites in an interactive and engaging manner.